By Boney Nathan

Edited by Quanita Nathan

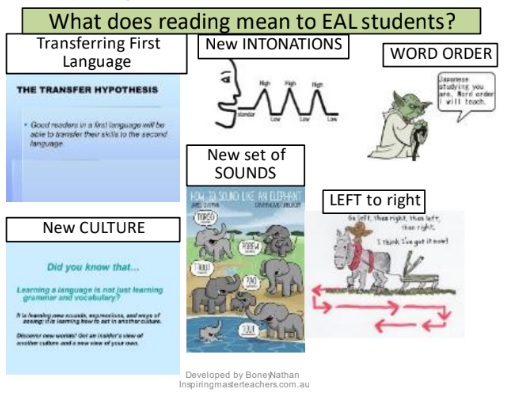

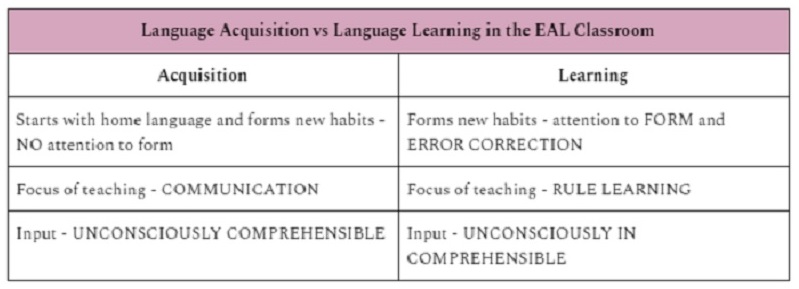

Learners of English as an Additional Language (EAL) are learning a language in the language they are learning. This means they are learning the behaviour and expectations of the target language in a language that they have yet to connect with. Nothing really makes sense in the beginning. Let’s take a look at what learning to read in a new language actually means to our EAL students.

First of all, reading for the EAL learner involves transferring skills from the first language. For this to happen, we are assuming that they can read in their first language. If that is not the case, the hooks needed to hang the new language on do not exist. Therefore, the transfer cannot happen and they are now acquiring the new language, much like how all children acquire languages from the ages of zero to five.

On top of that, the EAL learner needs to get acquainted with new or unfamiliar language conventions such as:

- set of sounds and sound groupings which may differ from their first language.

- intonation patterns and their meanings

- patterns of stress and pause

- sets of culturally-specific knowledge, values and behaviours

- grammar structure e.g., different word order in sentences

- reading from left to right la

In order for our EAL students to experience success in reading, we need to reflect on the reading materials that we choose. This is not an easy task as we not only need to meet the reading abilities of our students, we also need to consider age-appropriate materials so they engage and actively participate in our reading programmes.

We can begin with choosing reading materials with good visual cues that reflect the experiences, knowledge and interests of the learners. This can help to enable our EAL students to relate and access the stories more easily.

“Good pictures are as close to universal language as the world is likely to get…picture books are an invaluable aid to communication across linguistic lines”, (Reid, 2002, p. 35).

We can also use bilingual books, big books, stories with lots of repetition, class made books based on class experiences, and reading schemes with thematic interests. The key is to connect with the knowledge and experiences that our students already bring into our classrooms.

Furthermore, we need to continuously involve the EAL learner in a number of context-focussed reading experiences every day. These can include exposure to meaningful print in the immediate environment such as signs, charts, and labels around the classroom and school.

In order make reading a more meaningful experience, we need to model and deconstruct a range of texts to help our students develop their understanding of the organisation and language features of different genres. This can include taped reading from online resources, getting the better readers to tape themselves, or record ourselves and other teachers at the school. This will allow EAL students to hear some of the conventions of reading such as pauses, stops, intonations, and stresses. We can also use cloze activities to focus on comprehension or other aspects of language. Finally, wordless picture books have a whole lot of benefits for EAL learners but we will cover that in another blog.

Reference

Reid, S. (2002). Book bridges for ESL students: Using young adult and children’s literature to teach ESL. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.